Symbolism and Interpretation

Tarot's beauty lies in its intricate symbols, each bearing universal meanings. Anthropologically, a symbol is anything that stands for something else, and they are incredibly important in religious and spiritual practice— religious rituals are centered around the manipulation of symbols (Stein and Stein 2015). Within the Tarot, symbols like hearts and swords, colors, numbers, and animals convey messages that resonate on a profound level. Different Tarot decks can vary in imagery, and these changes reflect the creators' cultural and personal influences, reflecting fresh perspectives to traditional symbols (Keen Editorial Staff 2024; S 2023a).

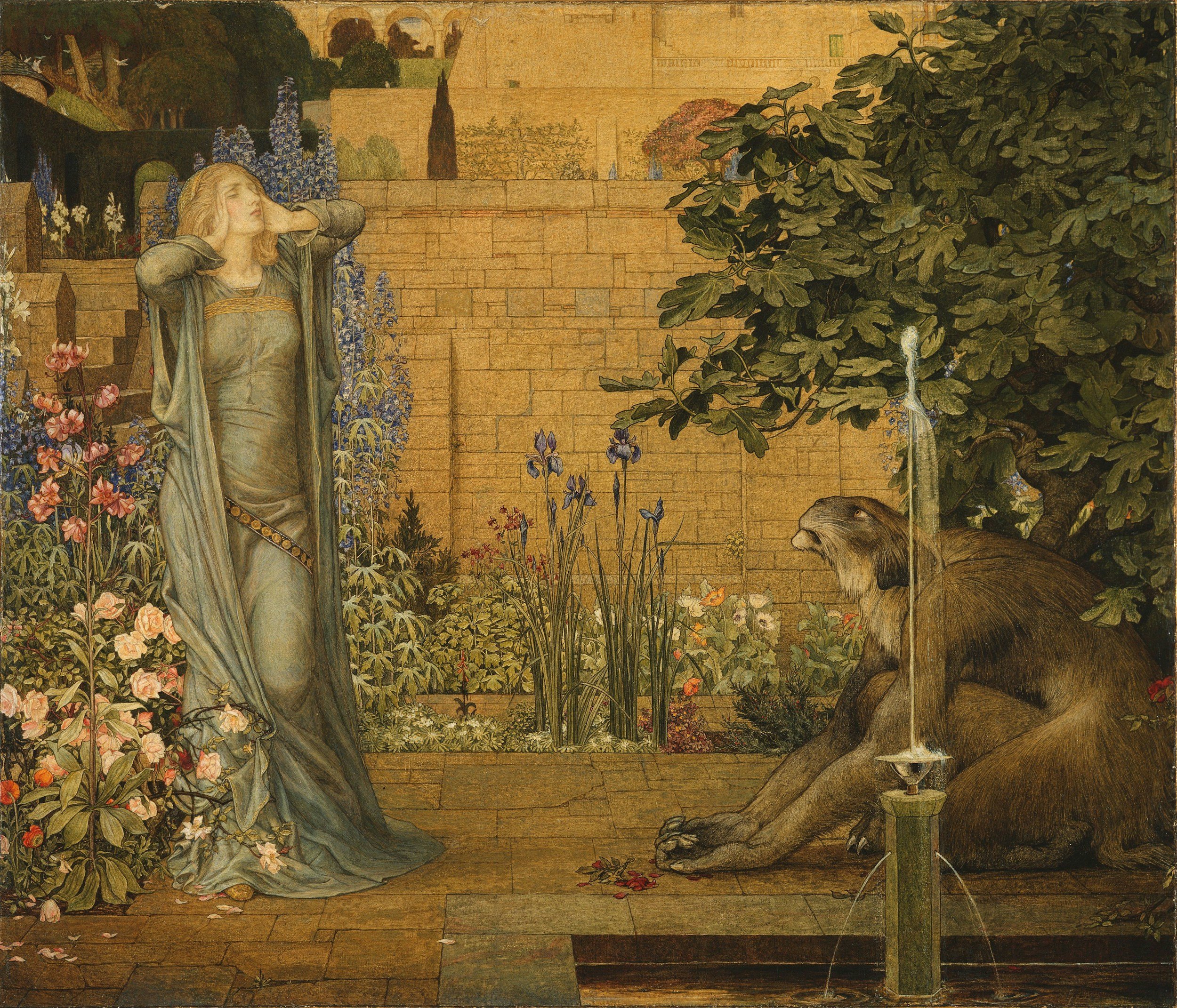

Over time, the symbolism of the Tarot became a language. Each color, character, and situation depicted on the cards is believed to be reflective of distinct facets of life (S 2023a). This section explores three of the most common symbols in the Rider-Waite and other classic decks, outside of the more obvious pip card suits, with a goal to understand their interpretation cross-culturally.

Common Symbols

-

Within Popular Tarot Interpretation

While The Moon is a popular card in itself, its image is seen frequently throughout . Similarly to how The Magician card depicts all four suits of the minor arcana carrying identical meanings (), this example shows how symbols tend to be fairly uniform throughout decks. Throughout

the deck, the moon symbolizes

Cross-Cultural Variations in Interpretation

meow meow

-

Within Popular Tarot Interpretation

meow meow

Cross-Cultural Variations in Interpretation

meow meow

-

Within Popular Tarot Interpretation

meow meow

Cross-Cultural Variations in Interpretation

meow meow

“There are a lot of symbols in the Rider-Waite deck that I don’t know, and so for me I’ve really always relied on what I first initiate with a reading. I feel like I sort of have my own symbolism.”

The Fool’s Journey

The Major Arcana are special cards found in tarot decks, setting them apart from regular playing card decks. These cards, starting with the 16th-century Tarot de Marseilles, consist of twenty-one numbered cards and a Fool card, which may be assigned the number zero in newer decks. The Fool represents a "hero" on a symbolic journey, leading to the term "The Fool's Journey." The Major Arcana images depict a Renaissance procession inspired by ancient Roman triumphs, with each card symbolizing a more powerful archetype than the last, forming a hierarchy as well as a chronological passage of time that sees The Fool through important universal life stages, lessons, and junctures that have the ability to completely alter our path (Manifestor 2020; Hume and Drury 2013). While tarot cards were originally meant for games, during the Renaissance, art often included deeper symbolism, as seen in the Major Arcana (Parlett 2009).

Tarot and Numerology

The numerology of tarot cards is a large and complex field of study with far too much to get into for this project. Although each reader has somewhat of a personal set of symbolism including numerically, a set of universal Much of this connection can be brought back to the work of 6th century BCE mystic and philosopher Pythagoras, who believed that numbers form the foundation of reality (Mack n.d.). Pythagoras's concept of numerical perfection, especially the significance of the number ten and the triangular arrangement known as the tetraktys, influenced Renaissance scholars and occultists. This fascination with numerology, rooted in the works of Aristotle, Plato, and Euclid, eventually shaped the structure of the modern tarot deck. The seventy-eight cards in the tarot deck reflect Pythagorean principles, as 78 is a triangular number (the sum of the first twelve numbers) (Louis 2009).

Turning Points in the Evolution of Symbolism and Interpretation

The tarot's imagery continues to evolve through history, reflecting cultural shifts.

-

The earliest tarot decks, originating in 15th-century Italy, consisted of 78 cards divided into two main categories: the Major Arcana and the Minor Arcana. The Major Arcana cards were added to a standard deck of playing cards. These cards were unique in that they did not bear the typical Italian suit marks but instead featured elaborate allegorical illustrations.

This period was experimental in card design, with some decks including queens in the series of court cards, which traditionally consisted of a king and two male figures (a knight and a page). In standard playing cards, these four figures were later reduced to three by the suppression of the queen, except in French cards, which suppressed the cavalier (knight) (Parlett 2009).

The trionfi, or trump cards, each bore a different allegorical illustration, likely representing characters from medieval reenactments of Roman triumphal processions. These processions were akin to modern festival parades, where each float or participant depicted a distinct, recognizable character. Originally, these trumps were unnumbered, requiring players to remember the hierarchical order of the cards. Their primary function was to act as a suit superior in power to the other four suits in the deck—a suit of triumphs, or “trumps” (Manifestor 2020).

The Minor Arcana closely resembled the structure of contemporary playing cards, divided into four suits. Each suit contained ten numbered cards, four court cards (typically a king, queen, knight/cavalier, and page [sometimes referred to as knave or valet]). The four suits in early Italian tarot decks were typically Swords, Cups, Coins (Pentacles), and Staves (Wands) These suits bore the traditional Italian suit marks and reflected a continuation of the imagery found in earlier card games.

-

The Tarot de Marseille emerged in late 16th century France, standardizing imagery such as dogs and crayfish under the Moon and the woman pouring water on the Star card. This deck became a foundation for later occult interpretations and divinatory practices, influencing fortune tellers and esoteric traditions in France and England, despite regional variations in Italy.

-

In 1781, Antoine Court de Gébelin linked Tarot to Egyptian wisdom and the Hebrew alphabet, catalyzing the French occult Tarot. Etteilla popularized card reading and divinatory meanings, while Eliphas Levi's 1855 synthesis of Tarot and Qabala integrated alchemy, astrology, and ceremonial magic, establishing a unified esoteric system that influenced later decks and interpretations.

-

The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, founded in 1888, placed Tarot at the center of its rituals and teachings, diverging from Levi by associating the Fool with Aleph and renumbering cards to align with astrological signs, which led to the Strength and Justice cards switching places. This system spread widely through the Waite Smith deck, popularizing new correspondences and divinatory practices in the English-speaking world.

-

The Waite Smith Tarot, created by A. E. Waite and P. C. Smith in 1909, combined Christian, Egyptian, and Golden Dawn symbolism. Its popularity was amplified by Waite's book "The Pictorial Key to the Tarot," leading to the deck's dominance in the Anglo-American Tarot tradition. This deck's imagery and divinatory meanings became standard, influencing numerous instructional books and solidifying the Golden Dawn's correspondences in modern Tarot practice.